These days, most documentaries are shot in HD, high definition. Seems to make sense, doesn’t it, since you can buy a high definition camera for just a thousand dollars! But does this mean that all HD is one and the same thing, and that you get as good an image with a thousand-dollar camera as with one that costs 50 times more? You guessed it, you don’t.

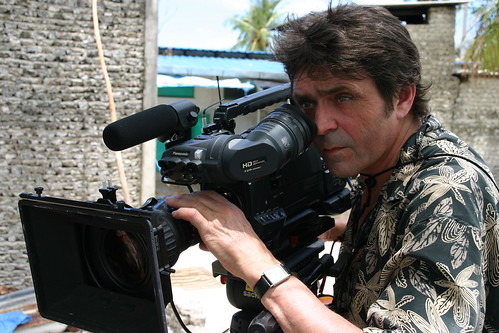

A few weeks ago I had the privilege of taking a course in HD workflow at PRIM, in Montreal, a resource centre for artists and filmmakers. (I am a member, we did the post-production for my most recent films there.) It was an opportunity to get an answer to my most pressing question: what does HD really mean, how do you know what quality you are really getting, and can you combine different kinds of HD formats without noticeable quality differences ?

So, in case you were asking the same question, here’s a short summary answer. The quality of a digital image is partly, but only partly, defined by the resolution, measured in lines of pixels. Standard Definition (SD) has 480 horizontal lines. The most common HD resolution is 1080 (horizontal) x 1920 (vertical) lines for a 16:9 image, but can be lower (720 for the vertical count is common) or higher (up to 4000 for a camera like the RED).

However, the actual quality of the image doesn’t depend only on the resolution. It also is a direct function of the compression, the size and nature of the image sensor, and the quality of the lens.

Compression is a way to encode the information to save space on whatever support the image is recorded on. It is expressed in three-part a formula as in 4:4:4 (uncompressed) or 4:2:2 (a $5,000 prosumer camera like the EX-1 which I use.) The inevitable cost of compression is a loss of definition and detail, and reduced margins for colour correction and visual effects in post production.

And the sensor. The smaller the sensor, the less detail you will get, and– counter-intuitively– the more depth of field you will get. More depth of field might sound like a good thing to the neophyte, but actually film makers tend to want the opposite, to achieve more of a ‘film look.’ (Main subject in focus, background out of focus, for ex.) Both Sony and Panasonic are just coming out with cameras that will make it possible to shoot video with a very limited depth of field, that will be another small revolution in video production.

With the help of PRIM’s excellent staff, we did some tests with the different cameras I use. To summarize the conclusion: the small and cheap HD cameras give a surprisingly good result, but you don’t get the same quality image as with a more expensive one. If you want to combine to two, the smaller/cheaper cameras should be used in good lighting conditions.

Thanks to Tobi Elliott for help with this post.