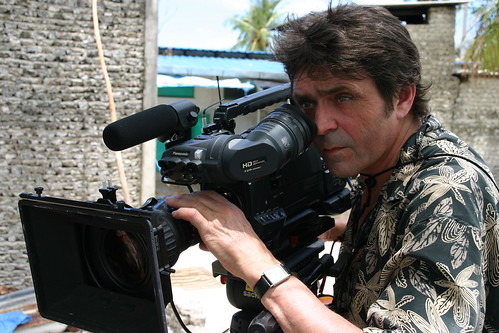

Ali Kazimi is an award-winning filmmaker. Since 2008, he has been researching stereoscopic 3D digital cinema at York University, where he is an Associate Professor in the Department of Film.

Q. Why is there this sudden groundswell of interest in 3D?

The current stereoscopic 3D is propelled by the exponential rise in digital technology in film production, coupled with the phenomenal success of James Cameron’s Avatar. Really, much of the growth in S3D is due to Cameron’s championing and use of digital S3D. Cameron himself did not come to S3D overnight, he spent the decade before Avatar experimenting with making underwater docs with different degrees of success. In fact, his underwater experience reveals itself not only in the very comfortable 3D experience he was able to deliver, but also in the flora of the imagined world which looks and behaves very much like underwater plants do.

However, it is his S3D experimentation that is critical to acknowledge and it is instructive in many ways – or to put it differently, S3D has a steep learning curve. The biggest challenge I feel is getting a grasp on the fundamentals of perception, how we see depth. Stereo vision, or ‘stereopsis’ as it is known scientifically, is the process by which the brain takes in the 2D images from the left and right eye and fuses them together into a single 3D image. However, stereopsis is only one way in which in the human brain perceives depth. We also use a number of other visual cues, called monocular cues, such as perspective or the familiar size of objects to determine spatial relationships.

Technically, S3D camera systems mimic the way we see. We use two cameras each offset by a certain distance, called the inter-axial (IA) distance, to generate two identical from images from slightly different perspectives, similar to those between our two eyes. The images have to be in perfect sync with identical focus, depth of field, colour and contrast, this is easier said than done. The mechanism for shooting stereoscopic 3D, known simply as rigs, therefore consists of two cameras either side-by-side or at right angles to one another with a partially silvered mirror at 45 degrees in the middle.

In terms of both composition and pacing there is much that is still unknown, filmmakers have to learn how to see the world around us with the z-axis in mind.

A couple of months ago just I saw a screening of shorts, commercials and music videos screened at the TIFF Bell Lightbox. The program, called ‘Selected Package’, had a wide range, from those with high production values to lo-tech DIY retro-inspired music videos. The latter were screened with the Red/Blue, anaglyph format. I have rarely come out of a screening with such acute eyestrain and headache. Once again, these music videos painfully drove home the difference between bad 2D and bad 3D, in that poorly produced S3D can be uncomfortable and even painful. Filmmakers have to recognize that their S3D work can have an immediate physiological impact on the audience. In fact this is the very reason why filmmakers have to step way back and truly re-examine how we see.

On the other hand, Wim Wender’s film Pina is a real masterwork and a true landmark in S3D filmmaking. In my view, the first feature film made solely for S3D, one that explores its immense possibilities with such inspired grace and virtuosity.

Wenders’ keynote address at our Toronto International Stereoscopic 3D conference was one of the most amazing artist talks, and a truly inspirational speech on how he came to 3D and how filmmakers should engage with 3D (read the transcript here). Pina is exciting because it was designed solely as a 3D film, whereas I have long maintained the almost all other 3D content is designed to work in 2D as well. Consequently there can only be limited exploration of a new cinematic language. More on Pina a bit later.

What is it that you have to learn? Theory or hands-on?

On the technical side, digital projection has made it possible to deliver a pretty seamless 3D experience, it is another matter that many cinemas don’t have proper projectors resulting in relatively dimmer image. Of course this is the last but crucial stage in the entire digital workflow.

In some ways the ‘Avatar effect’, as I often refer to it, has been a mixed blessing. The studios and the television manufacturers all jumped on the bandwagon. S3D sets are now increasingly on the market and prices are coming down fast, the problem is the dearth of content. To create content one needs more than tech, training and accessibility is critical. As I have said earlier, S3D has a steep learning curve and there are no short cuts, it will take time to develop a critical mass of filmmakers and technicians.

The most critical position is that of the stereographer – a stereo expert who should ideally be at least consulted during pre-production, who is on the set during production working with the camera rig and who then again at least consults through post-production and during the final colour and stereo-grading. Stereographers are hard to find, in this new field many people claim to be one after doing a workshop or two, one has to be really careful. Errors made in production such as the depth of a shot are impossible to “fix in post”.

Thanks to Tobi Elliott for her help with the blog.