The other day I went to see two exceptional films in 3D at the Festival du Nouveau Cinéma in Montreal. Millions of words have been written already about Wim Wenders’ film about the amazing choreographer Pina Bush, and I don’t have anything to add.

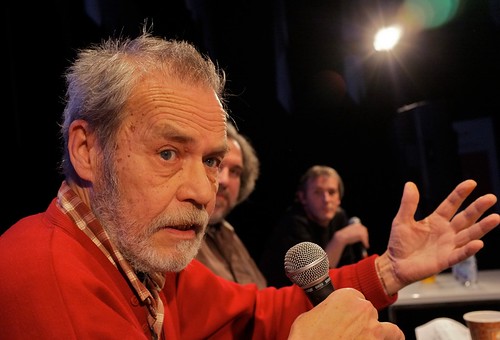

But that film was preceded by another extraordinary dance film, Philippe Baylaucq’s ORA. Shot with infrared cameras which capture only the heat of the bodies, with no light source whatsoever, it creates totally original images of translucent bodies dancing to a score by composer Robert Marcel Lepage. Philippe had chosen this project for his two-year residence in the National Film Board of Canada’s French program. I asked him what motivated this choice.

“The project started with the idea of marking the first century of abstract painting. I re-read Kandinsky and wanted to explore that period of painting and set design (Diaghilev, etc) when the human figure was still present in environments that were becoming increasingly abstract.

Initially I was interested in exploring the relationships between the human figure, dance, colour and space. I wished to work again with my friend and colleague dancer-choreographer José Navas and met up with him before applying to the NBF for one of their two year residencies. I was lucky, I got in and began to read up on my subjects. Soon I became aware of what was being done at the NFB StereoLab where I was blown away by what I saw, by what I was shown by Munro Ferguson. It became clear to me then that my two years spent at the Board would have to lead to a film that could be done there and nowhere else. Hence the 3D.

I had a full year of tests before opting for a world technological first: 3D thermal cinematography.

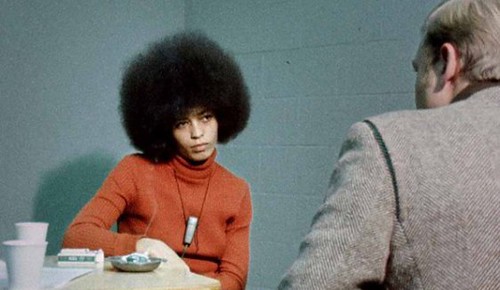

One does not really tell stories in the linear sense with dance. One does however have to be aware that most film spectators expect a storyline of some kind. I started with the title of one of Paul Gauguin’s most famous paintings: Where do we come from, who are we and where are we going? For optimal formal freedom, I wanted my dancers to evolve in a non-naturalistic setting, giving me the chance to be more audacious with gravity, depth, light, texture, movement.

From then on, I was interested in working in the “Norman McLaren” fashion which is to say that the filmmaker is led to his story-line through the interaction with the tools, materials and technologies that he is exploring. Our work with thermal imagery led us to discover very interesting phenomena that spoke of larger themes such as Darwinian evolutionary theory and classical myths such as Prometheus and Narcissus. Slowly, through the fundamental research with the technologies, a story immerged and eventually a film… It was fascinating.

2. A lot of the comments have been about the striking technical achievement, but the structure of the piece, with the music and choreography, must have been a considerable challenge. How did you work with composer, choreographer, dancers?

Working with me on this kind of subject is a trapeze act without a net. From the start, everyone becomes aware of the exploratory aspect of what we are doing. People are generally stimulated by uncharted ground, it gets them out of their routine and forces everyone to be ingenious, to extend further out and test their talents. Again I was blessed with many many inspired collaborators. I worked with people that also work in the documentary field and this is very important because it signifies that they know what it means to be open to chance and aware of what is there, in the world and not strictly on the pages of a script.

The film was loosely written, but my main collaborator José Navas, his magnificent dancers, my DOP Sebastien Gros, my musician Robert Marcel Lepage, my sound designer Benoît Dame, my editor Alain Baril, and many others, everyone was open to the idea that this piece was going to evolve until the very end of the very last stages of post production.

This requires a lot of patience and a very open minded producer. René Chénier did a remarkable job accompanying me through this open ended process. Despite the cutting edge, high-tech aspect of our novel technology, we tried to keep our feet on the ground and not get swept away by the myriad possibilities that both the camera and postproduction computer input might provide us. We tried to never lose sight of the organic, human aspects of our on screen subjects: the dancers. They are all that we see as they at once both the subjects and the light sources that define the subjects: they carry the light, they are the light.

The film is probably one of the very first films to have ever been shot without a single light source: no fire, no sun, no electricity; only heat, the heat of the body, biological light, the light of living things, the light of life itself.

Thanks to Tobi Elliott for her help with the blog.