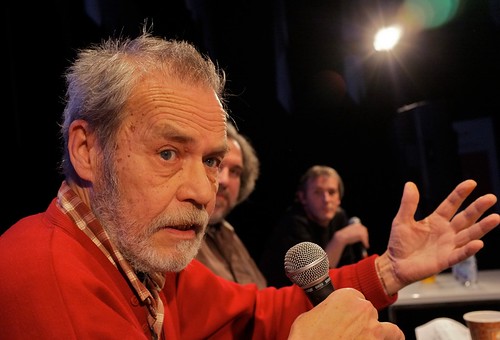

Jacques Leduc

This past weekend I went to some screenings at the annual Rendez-vous du cinéma québecois and caught up with some documentaries I missed last year. The RVCQ offers a dazzling combination of riches: fiction and docs, animation and multi-media experiences, screenings, workshops, panels and round tables. My friend and constant co-worker Martin Duckworth was impressed by a workshop with Montreal filmmaker Jacques Leduc.

Jacques Leduc began working as a cinematographer and director in 1965. His debut as a director was with the short Documentary Chantal en vrac (1965). Leduc followed this with his first feature fiction film two years later, Nominigue… depuis qu’il existe (1967) and then his first feature documentary film Cap d’espoir (1969). For the next two decades in the 70’s and 80’s, Jacques Leduc continued to work films with the NFB. During this time he collaborated on the NFB film Chronique de la vie quotidienne(1978), a series of 8 films. These varied in length from 10 to 82 minutes, in a cinema vérité style of observing the lives of ordinary people. He left in 1990 to become a freelance filmmaker, soon making the film La vie fantôme (1992) that won the Best Canadian Film at the Montreal World Film Festival. Since then he has been collaborating with other filmmakers both as a director and a cinematographer.

Here is what Martin has to say about the workshop:

Rendez-vous with Jacques Leduc was an hour of nostalgia for the end of a golden era (late seventies) when it was possible to get a film programmed at l’ONF with a proposal of a page and a half, and then take a year to make it. A time when there was a collective conscience among Quebec film-makers of a culture to celebrate. A time when the candid-camera style that started with Lonely Boy had reached its peak in the films of Gilles Groulx and Pierre Perrault, leaving room for blending it in with some of the more controlled “cinematic” style then being introduced in Quebec features–dollies, cranes, long takes. A time when documentary film crews could easily blend with crowds, free of the fear and suspicion that has tied documentary crews these days to the laborious task of getting people to sign release forms. The collectively signed films that were shown prior to the discussion (“Chronique de la vie quotidienne”) were born in the tavern where Film Board personnel went for lunch. Jacques Leduc coordinated ideas, crews, locations and editing, and was grateful for the support given by producer Jacques Bobet to a production without a script or completion schedule. One of our most original directors, Robert Morin (Requiem pour un beau sans-coeur (1992),Quiconque meurt, meurt a douleur (1997), Operation Cobra (2001)), credited the series with inspiring him to start up a video cooperative which has been important to many Quebec filmmakers. Fiction director Louis Bélanger (Nightlight (2003), The Timekeeper (2007), Route 132 (2010)) talked of how moved he was by the respect that Leduc obviously had for his characters. And DOP Pierre Letarte who worked for many years at the NFB stressed that it was not the equipment or the shooting style that gave the series its humane quality, but the close relationships that the crew established with the characters.

Rober Morin

Louis Bélanger